In the city of Timbuktu, the fundamentalist Islamist group Ansar Dine (“defenders of the faith”), wearing black flags to cover their faces, decimated shrines, Dogon wood sculptures, and World Heritage sites, considering them to be examples of idolatry, a sin in Islam. Nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Film, Abderrahmane Sissako’s (“Bamako”) Timbuktu is a series of vignettes depicting the reactions of the people to the harsh laws of the Islamists seeking to impose Sharia law across Mali. Written by Sissako and Malian co-writer Kessen Tall in her feature debut, the film is a lament for the legendary land in which the director lived as a child, and a heartfelt plea for the world to return to sanity.

Set in Mali in 2012, the film begins and ends with running. In the opening scene, pursued by men in a jeep who are determined to break its spirit, a graceful gazelle runs across a pristine desert. The men are doing “jihad,” periodically shooting at the animal with assault weapons as one of the hunters explains the strategy: “Don’t kill it, tire it,” he says, “That is how we win.” The film centers on Kidane (Ibrahim Ahmed), a peaceful Tuareg herdsman who lives with his wife, Satima (Toulou Kiki), their 13-year-old daughter, Toya (Layla Walet Mohamed), and adopted son, Issan (Mehdi A.G. Mohamed) in a tent close to town which is now run by the Islamic police.

The family, like others, is forced to live under rules that prohibit smoking, video games, Malian and Western music, and football, though the Jihadists are hypocritical in flouting these same laws themselves. As Abdelkerim (Abel Jafri, “Juliette”) and his partner Omar (Cheik A.G. Emakni) drive around the village intimidating people, Abdelkerim sneaks off to smoke cigarettes, unaware that Omar knows his secret. He also flirts with a married woman even though her husband is present, a violation of Sharia law. Though the laws apply to everyone, women are more often than men on the receiving end of the punishment. They must cover their head with veils and wear gloves whether or not it makes sense for them in their profession, and stoning and lashing are ordered for adultery and other crimes.

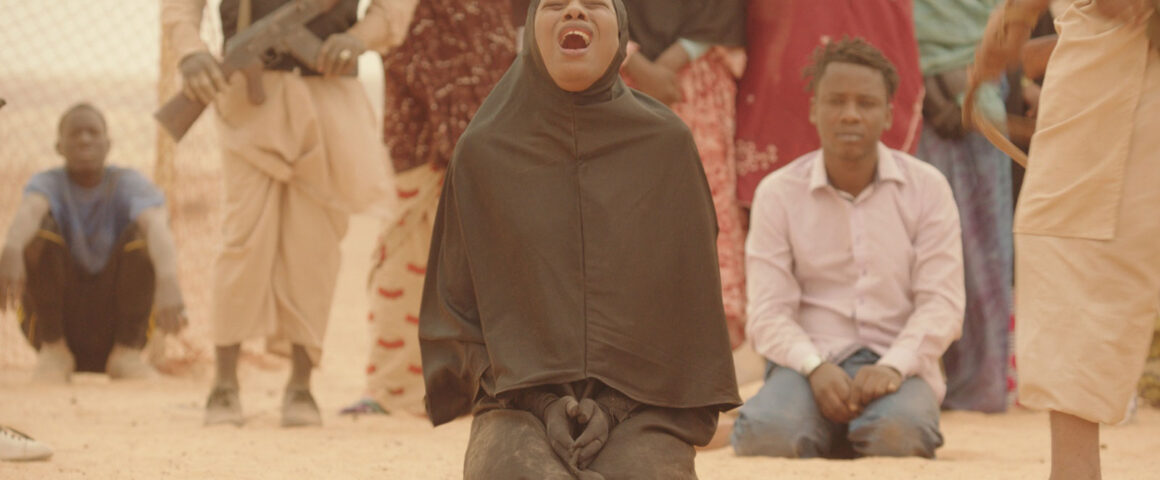

Based on an actual incident, a couple, found guilty of adultery, are buried in sand up to their necks, and then stoned to death. Not everyone supports the fundamentalist’s rule, however. When the militants seek to enter the temple with their weapons, the imam (Adel Mahmoud Cherif) tells them: “Stop this. You cause harm to Islam and the Muslims, you put children in danger in front of their poor mother, you even hit the mother of two children without any good reason.” He asks, “Where’s leniency? Where’s forgiveness, where’s piety, where’s exchange? Where’s God in all this?” Abdelkerim has no answer but stares silently at the ground.

The central confrontation is between Kidane and a local fisherman (Amadou Haidara who kills Kidane’s prize cow “GPS,” when he became tangled in his fishing nets. Kidane, seeking revenge for the loss of his cow, wrestles him to the ground but his gun goes off and Amadou is killed, a crime for which Kidane is arrested and sentenced to death. While Timbuktu does not poeticize injustice, many visual moments are nonetheless works of art: Kidane walking across the water like a Christ figure after killing Amadou and Jihadists shooting into a bush that resembles a female organ.

Despite their slogans and bravura, however, Sissako depicts the terrorists as insecure in their beliefs. A young man, presumably a former rapper, talks to a video camera, attempting to describe his conversion to the militant form of Islam that the Jihadists represent. Even with prompting, the boy is unable to articulate his feelings and simply lowers his head, unable to verbalize the dogma. In a memorable scene, boys play a soccer game without a ball, running up and down the field kicking dirt as if to defy the authorities. Though Sissako does not raise any false hopes about the future with Timbuktu, it should be noted that the Jihadists were driven out by French forces after one year in power, and, if the film is correct, much of their success may have been due to the resilience and inner strength of the women of the village who never tired and refused to run.

'Movie Review: Timbuktu (2014)' has no comments