“These things cannot be long hidden: The Sun, the Moon, and the truth” — Buddha

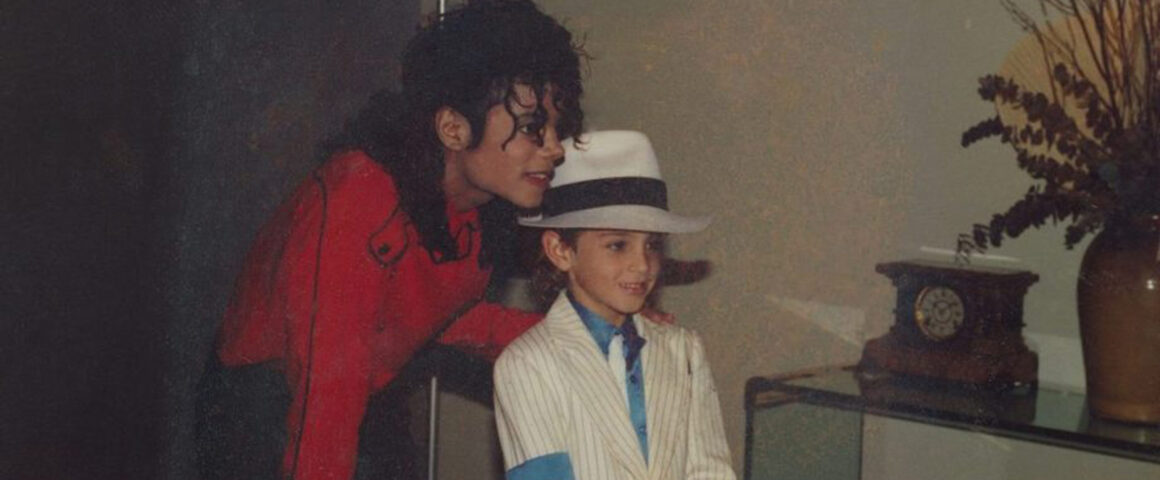

Dan Reed’s (“Three Days of Terror: The Charlie Hebdo Attacks”) gripping two-part documentary Leaving Neverland is not an easy watch, nor was it meant to be. While it may not ultimately be considered to be great cinema, it is a powerful and provocative film that is likely to leave you emotionally drained. The film chronicles the odyssey of two men, Wade Robson and James Safechuck, now in their thirties and forties, who claim that they suffered sexual abuse at the hands of pop music superstar Michael Jackson beginning when they were children and continuing through adolescence. The convincing accounts of both men, supported by family members, constitute the entire film with the late Michael Jackson presence felt through photographs, videos, and correspondence.

For the record, Jackson’s estate denies the allegations made in the documentary and are now suing the film’s producer and director. Robson and Safechuck’s stories are perfectly corroborated, however, even though they met Jackson years apart and under very different circumstances. Robson from Australia and Safechuck from Simi Valley, California were aspiring performers looking for a breakthrough opportunity to advance their careers. Wade was a fan of Jackson from a very young age, learning to mimic his dance steps and performing moves from “Thriller.” Safechuck, while not a huge Jackson fan, also wanted to have a career as an entertainer.

When the seven-year-old Wade won a dance contest by performing tracks from “Bad,” he won the opportunity to meet with Michael Jackson when the singer visited Australia. For Wade, their, performance together on stage was a dream come true. On a subsequent visit to the U.S., Robson was invited to Jackson’s Neverland Ranch near Santa Barbara, California and quickly became one of Michael’s favorites. At the ranch, Wade had unlimited access to amusements: toys, games, movies, candy, almost anything they wanted and he bonded with Michael in a fantasy of unlimited pleasure. In fact, their friendship became so much a part of Wade’s life that his mother and sister moved to Los Angeles so that Wade and Michael could be together anytime he wanted.

For Safechuck, it was a different path but the destination was the same.

Jimmy, then nine, appeared in an iconic Pepsi Cola commercial in the 1980s in which Jackson was also featured. The commercial led to a friendship with both Jimmy and his family in which Michael took them to Hawaii on vacation, invited them to his Encino estate, and eventually visited their home in Simi Valley. When Jackson confessed to Safechuck that he was lonely and didn’t have any other friends, the suggestion of having a “sleepover” was not far away, much to the chagrin of Jimmy’s mother. According to Robson, physical contact began gradually with hugs and kisses but soon escalated into “sexual stuff,” as graphically described in the film. What went on, however, does not fit our pictures of what abuse looks like.

As Wade and Jimmy tell it, they did not see their having sex together as abuse. Michael told them that this was the way people express their love for each other and they believed what he told them. According to Safechuck, Jackson even simulated a marriage ceremony, complete with a diamond ring and wedding vows. On the other hand they were told that if anyone ever found about what they were doing together, they would both go to jail for the rest of their lives, a very contradictory message. Though they loved Michael and felt that he loved them as well, they were cowed into silence and did not feel it necessary to tell their parents what was going on behind closed doors. The film describes how Michael attempted to poison the boys’ relationship with their parents while, at the same time, staying close to them to make sure that Wade and Jimmy would always be accessible.

Unfortunately, the parents did not ask questions and trusted Michael enough to believe that what was going on was playful and innocent. When they discovered the truth, however, their feelings of guilt were devastating. Although both men testified for the defense at Michael Jackson’s 2005 trial for sexual abuse, Robson describes how fear played a major role in the lies that he told in court and later to his therapist. It was only when both had their own kids that they realized the true nature of what they had gone through and became clear that their job as parents was to protect their children.

The second part of the film deals with the process in which the two men begin to cope with their feelings of anger, shame, self-hatred, and guilt. For them, there is no closure and there may never be. They know that it will require years of work to understand what lay behind decades of suppression and denial. Whatever position you come away with from the film, Leaving Neverland is an important documentary, even a necessary one, and should be widely seen and discussed. It is a disturbing experience, however, and no effort is made to hide the fact that the pain will remain for those involved long after the film is forgotten, yet it is a subject that transcends Michael Jackson and has a broader relevance to the issues taking place today in the arts, schools, churches, and families.

While not dismissing the devastating damage that Jackson caused, we should also not overlook the contribution that he made to millions of people around the world, whose love for him has not diminished over the years. We should also not fall into the trap of calling him a “monster,” but realize that he was a human being who was deeply flawed but with whom we share a common humanity. Forgiveness of the abuser may or may not occur for Robson and Safechuck, but if the process ever comes to that stage, it will not be the end of healing but only the beginning. While the film suggests that love can exist side by side with pain, the challenge for them and for us is to go beyond the pain and remain open to the possibility of a world of purity, innocence, and grace.