Coming after the failure of singer/songwriter Paul Simon’s solo album Hearts and Bones, and the messy breakup with Art Garfunkel, his 1986 album Graceland was the most successful of his career and, to many, the artistic highlight. Simon’s return to South Africa to commemorate the 25th anniversary of Graceland is documented in Joe Berlinger’s exuberant Under African Skies. The film includes original footage of rehearsals and performances from past and present including an emotionally-charged appearance on Saturday Night Live, interviews with prominent musicians and political leaders, as well as disturbing images of police brutality during the period of Apartheid.

It is a fascinating documentary that is not just a standard puff piece but one that deals with the complex relationship between art and politics. Berlinger records the playful give and take of the recording sessions and how the songs developed in Simon’s mind from the influence of African bands such as Stimela and the acapella singing of Ladysmith Black Mombazo. Extensive footage from the original recording sessions is interspersed with actual performances both from 1986 and the present day (the latter a pale imitation of the original). Though the reunion is a celebration of friendship and even love (Joseph Shambala of Ladysmith Black Mombazo says that Simon was “the first white musician that he ever hugged”), the film does not duck controversy.

The issue is the antagonism of anti-Apartheid activists stemming from Simon’s 1985 South Africa trip to recruit black musicians that broke the United Nations cultural boycott. There is a lot of discussion in Under African Skies, perhaps more than music, but it is relevant to the important issues the film raises. Berlinger sets up an exchange between Simon and Dali Tambo, a member of the Artists Against Apartheid that allows each side to present their case without rancor or bitterness. Both present convincing arguments and the director wisely does not attempt to skew the debate towards one side, though it is seems fairly easy to guess where his feelings lie.

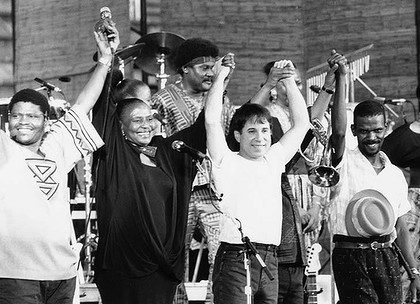

Weighing in on the issue are prominent personalities such as Harry Belafonte, Hugh Masekela, Miriam Makeba, Oprah Winfrey, Whoopi Goldberg, David Byrne, Philip Glass, Quincy Jones, Paul McCartney, and others. While Graceland may not have directly contributed to the end of Apartheid, Simon contends that the music they produced was an instrument of healing that ultimately was more powerful and of greater political benefit than the boycott. Helping to introduce South African music to the world, he says, demonstrated that another way was possible in South Africa and that the real story was the impact that the project had on the black musicians. Their comments in the film expressing humility and gratitude for the opportunity they were given are the emotional high point of the film.

Referring to the African National Congress (ANC), Simon asserts that the artist should not be dictated to by politicians no matter what their cause, and if the ANC wanted to control what he sang and who he sang with, they would be no different than the government they were fighting to overthrow. Isolated and oppressed in their home country, when the ANC ordered the musicians home from their world tour, the guitarist Ray Phiri, told the ANC leadership, “I am a victim of apartheid. It is not possible to victimize the victim twice!” Tambo, on the other hand, counters by saying that Simon’s “appropriating” and using black South African musicians for his own ends is exploitation and, in the context of the UN cultural boycott, endangered the efforts to end Apartheid.

Though obviously staged for dramatic effect, the back and forth argument between Simon and Tambo is conducted with restraint and respect and each point of view is given a full hearing. With the 1992 release of Nelson Mandela that signaled the end of Apartheid and the coming to power of the ANC, the controversy has faded but Simon’s breakthrough album remains an exhilarating artistic achievement that has lost none of its power after twenty five years, and joyous songs such as “You Can Call Me Al,” “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes,” “The Boy in the Bubble,” and “Graceland” still have the power to move.

Under African Skies is a must see not only for music fans, but for anyone who does not rule out the possibility of being inspired. Though the debate about the relationship between art and politics is not resolved and may never be, the words and the pulsating music of Paul Simon’s song “Under African Skies” performed with Miriam Makeba at a concert in Zimbabwe delivers a message that is loud and clear, “This is the story,” the song says. “Of how we begin to remember; this is the powerful pulsing of love in the vein; after the dream of falling and calling your name out; these are the roots of rhythm and the roots of rhythm remain.”

'Movie Review: Under African Skies (2012)' have 2 comments

November 30, 2012 @ 9:21 am koshkalady

I always felt Paul Simon exploited the situation for personal gain.

December 1, 2012 @ 10:16 am insecticide

But where is Art Garfunkel?