If Joel and Ethan Coen’s “The Big Lebowski” is a stoner neo-noir comedy based on a misidentification, then John Turturro’s sort of spin-off The Jesus Rolls is a road movie based on a lack of destination. Not that any comparison between the two films is fair because they are very different. “The Big Lebowski” takes place in the weird skewed universe of the Coens and The Jesus Rolls in a more mundane setting. And yet, plenty of odd things certainly happen in this film.

From the opening scene the tone is set. A sequence of long shots invite the viewer into Sing Sing Correctional Facility as guitar music plays, before we see the musicians (the Gipsy Kings) appear in a cell, playing a jaunty tune as Jesus Quintana (Turturro, “Landline”) leaves prison. This opening neatly summarizes the tone of the film: quirky and keen to subvert expectations. After bidding a curiously fond farewell to the prison warden (Christopher Walken, “Father Figures”), Jesus is met by long time friend Petey (Bobby Cannavale, “Motherless Brooklyn”). From there, events escalate, spin out of and then back into control.

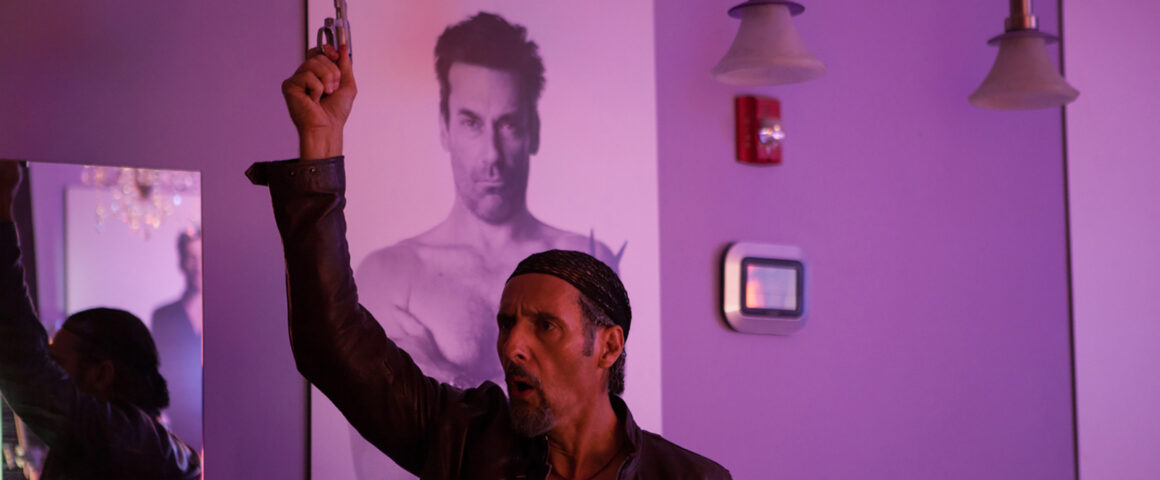

Alongside Jesus and Petey, The Jesus Rolls boasts a wacky cavalcade of characters. There is Walken’s cameo as the Warden, Paul Dominque the Hairdresser (Jon Hamm, “Bad Times at the El Royale”) who makes a point of demanding “Who is the hairdresser?” when he confronts our hapless and befuddled heroes. Audrey Tautou (“The Trouble with You”) plays Marie, a French hairdresser in New York (obviously) who travels with the boys both geographically and in other ways. Jean (Susan Sarandon, “The Last of Robin Hood”) is a random prison parolee who hooks up with the boys briefly because she has nothing better to do, while her son Jack (Pete Davidson, “Set It Up”) is the third person in the film to leave prison and turn out to be different from how he seemed.

Aside from Marie, most of these characters appear only briefly. Nonetheless, Turturro integrates them into the drama in a way that feels organic and unforced. This is part of the film’s somewhat freewheeling style: Much as the characters move between stolen cars and curious locations, so does the film veer from quirky set piece to peculiar conversation. Striking moments include Jesus styling and profiling, a man shot nearly in the testicles, a random overhead shot of Marie sunbathing topless, chases involving bicycles, cars and a train. Along the way, there are minor references to “The Big Lebowski,” most obviously Jesus’ line about pulling the trigger until the hammer goes “click.” We also see Jesus’ iconic lick of the bowling ball and indeed a bowling scene. However, anyone waiting for these moments will be disappointed beyond these few, as bowling has no significance to the plot and there is none of the Coens’ wacky humor.

Instead, what is to enjoy here is Turturro bucking certain movie conventions, especially in respect to sexuality. The close friendship between Jesus and Petey could be a standard “bromance” complete with banter that verges on homophobia, but instead Turturro subverts expectations with his amusing and often charming treatment of male relations. There are several shots between Jesus and Petey as well as between other male characters that look as though they are about to kiss. Heterosexual men walk with their arms around each other, share a bed and a shower. An offer of homosexual sex between men who are presented as straight complicates expectations of sexuality in film, as do almost and actual threesomes. Furthermore, the arguments between Jesus and Petey have the flavor of a lovers’ quarrel.

The film’s interest in sexuality goes further, as Tautou’s Marie has never achieved sexual climax and her arc through the film is something of a sexual odyssey. Jesus is also presented as a strange sort of gentleman. He dances with a random woman but there is no successful pick-up, and he seems to have a fondness for fine food and wine. Despite his and Petey’s tough guy bravado they are clearly sensitive souls, often displaying the insecurity of alpha males. Their symbiosis extends to similar attire and creating an unconventional family with a seemingly idyllic life in the woods. Wide shots of beaches and water as well as meadows in sunlight are interspersed with car thefts. The idyllic framing continues right up to the final shot, hinting at the convention of criminals wanting to escape from it all. But there is no final score and scarcely any planning on the part of our protagonists, who drift through the plot with little sense of direction.

The performances are typical of the film as a whole, as Turturro is an unfussy director. He and director of photography Frederick Elmes conduct the film largely through wide shots and close ups, with the occasional stylistic flourish. Perhaps unsurprisingly for a road movie, there is an active camera while driving, including many travelling shots of vehicle motion and especially shots through the windshield which is also used in one of the film’s more alarming set pieces. This restricted view is illustrative of the whole film as, while there is violence, it often occurs off screen: A character shoots to the right of the frame; at other points gunshots are heard but not seen.

The omission of impact as well as character goals ties into the film’s conceit of unexpected consequences. The characters travel but cycle back to where they came from. What comes around goes, or perhaps rolls, around. This is not a road movie about the journey, but about the relationships of the people on it, which often turn out to not be what you think. Despite this, The Jesus Rolls is unlikely to stick in the memory, offering only mild diversion. Ultimately, the viewer will either roll with it, or won’t.