A mixture of harsh industrial sounds and dreamier synth beats power into the room as neon shapes move kaleidoscope-like before our eyes. This is Daniel Isn’t Real, an immersive experience bathed in sound and visuals. We open to a shot of the cosmos which then dissolves into a present-day coffee shop; a juxtaposition of the domestic and mundane with the fantastic which immediately sets the theme of duality and doubling that will run throughout the film. Based on the novel “In This Way I Was Saved” by Brian DeLeeuw, director Adam Egypt Mortimer’s aim is to reverse the trend of still, grey horror and pump it full of noise and color to evoke an anxiety-filled experience.

The story centers on a boy named Luke (Griffin Robert Faulkner, “It Comes at Night”) who witnesses a murder at the aforementioned coffee shop which coincides the arrival of his imaginary friend, Daniel (Nathan Chandler Reid). With swept back hair, slick style and a confident attitude that conflicts with Luke’s more carefree appearance and childlike innocence there is a sinister edge to Daniel’s presence right from the get-go. True to our suspicions, Daniel reveals himself as a force for danger and destruction — a fact which is brought to light when he persuades Luke to carry out a plan that results in his mother, Claire (who is herself, dealing with severe mental health issues) insisting there is no longer a place for Daniel in their lives. Luke is ordered to banish his friend within the confines of a doll’s house, an object symbolic of the mind. Daniel’s occupation of Luke’s psyche is depicted through a continuing rattling noise that begins to grow quieter as we transition to a shot of an older Luke who has successfully driven his playmate out. However, Daniel proves that he is as irremovable from Luke’s life as he is from the film’s title when he makes an unwanted reappearance.

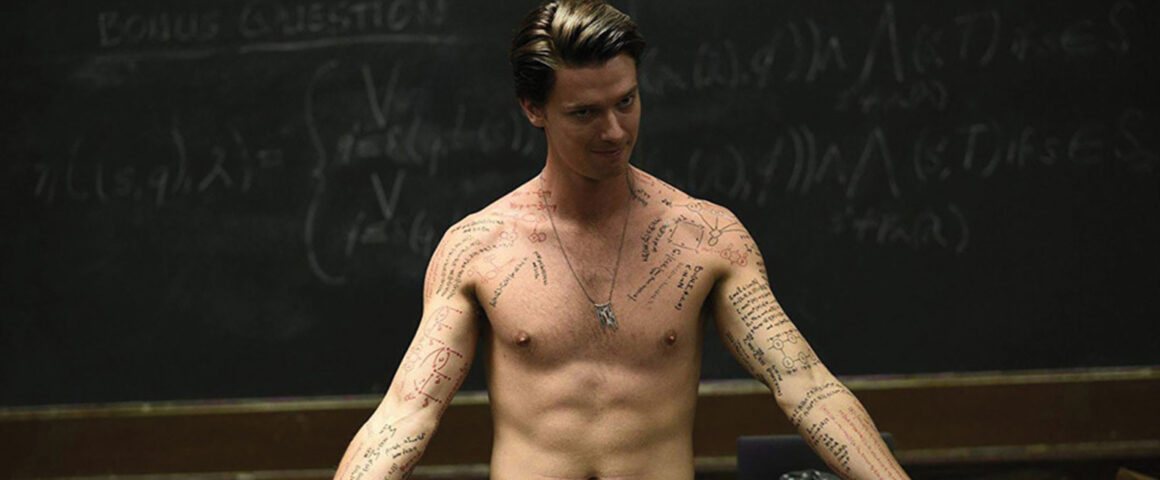

Now an adult, Daniel’s (now played by Patrick Schwarzenegger, “In This Way I Was Saved”) unpredictable behavior intensifies and we see that he is ultimately a sabotaging force, seeking to ruin any positive aspects of Luke’s (now played by Miles Robbins, “Halloween”) life; he secretly uses his phone to text friends in order to construct unwanted social situations, encourages Luke to binge drink and be sexually promiscuous in a way that is out of character, dissuades him from taking medication and almost gets him expelled from university.

The inclusion of mirrors is used throughout Daniel Isn’t Real to indicate a doubling, a pairing or even a split at various intervals. This theme is extended to include the notion of dualism which is also an inherent thread throughout. Claire (Mary Stuart Masterson, “The Insurgents”) smears the mirrors in her house because she doesn’t like what she sees, Luke stares into a classroom window struggling to identify with his own reflection and later dons a mask in order to scare his room-mate Richard (Andrew Bridges, “ReRun”), a gesture which is followed by a shot of him and Daniel laughing beside one another that resembles a mirror image or reflection.

When Luke suffers a stress induced seizure, he visits a therapist, expressing his fears that he will evolve into his mother. Notably, he plays Daniel down citing it as “pathetic kids stuff,” but his therapist’s advice is to embrace his imagination rather than resist it. The power of imagination is further referenced when Daniel dismisses Luke’s books on Symbolic Logic Structure, commenting on how he “used to be bursting with imagination.”

Committed to a psychiatric hospital, Claire tells her son during one of his visits she was 20-years old when she first began to experience mental health issues. It’s no coincidence that this is the age which we presuppose Luke to be, suggesting that he is hurtling towards his greatest fear. When she describes her experiences they mirror that of Luke’s — “It’s like being plugged into an electric socket,” she tells him. Intuitively, she is able to determine that her son is in need of help and is the only one able to identify this precisely because she is also the only one who knows what he is going through.

Things take a more positive turn when Luke meets Cassie (Sasha Lane, “Hearts Beat Loud”), an artist with whom he will form a loving and positive relationship. Daniel begins coaching Luke on how to converse with his new love interest as Luke tries to eschew the continuous interruptions and be true to himself. The tensions between friends are felt at their keenest during a scene in a bookshop where Luke takes numerous cues in the form of book quotations (notably one is from “Where the Wild Things Are,” a no doubt purposeful choice). Cassie is duly impressed, but when she takes out a copy of the Bible, Luke goes against Daniel’s direction. Rather than quoting the verse he opts for a crude limerick which draws laughter from Cassie. However, this moment is cut down immediately by Daniel regaining power with Luke proclaiming “Amen” to a line about only worshiping one God. Daniel’s power it turns out, is not impenetrable as he does not interject during an intimate scene between the young lovers, the inference being that his silence is due to Luke feeling truly content in the oneness of these moments.

Despite his new-found relationship, Luke’s episodes intensify and his therapist decides to take a different approach by visiting him at his mother’s apartment to undertake a hypnosis. This is played out against a minor subplot which although unnecessary does not alter the overall experience. We then alternate between two worlds; one of Daniel in the present and the other of Luke plunged into a realm of dark fantasy that will remind British viewers of a certain age of the ground-breaking children’s program “Nightmare.” Beautiful neon colors are contrasted with dark doorways whilst choral music reminiscent of Philip Glasses unforgettable score for “Candyman” adds to the ethereal and other worldly experience. At one time or another we have all felt an overwhelming sense of bombardment, disorientation and uncertainty about ourselves as a result of the constant and conflicting messages we receive. Daniel Isn’t Real is a meditation on the theme of hyper connectivity which fills our lives with stresses and in this respect it is more vital than it might at first seem.