In memoriam: American Democracy

Mystics heal borders. They are the frontiers’ physicians. Surgeons of the lines. As scalpels come their words, their prayers that no one hears, for no one knows silence better than those whose words shall meet no ears. As scalpels come their prayers, immersed all in flesh and blood, in infatuated vessels that are opened as they are torn.

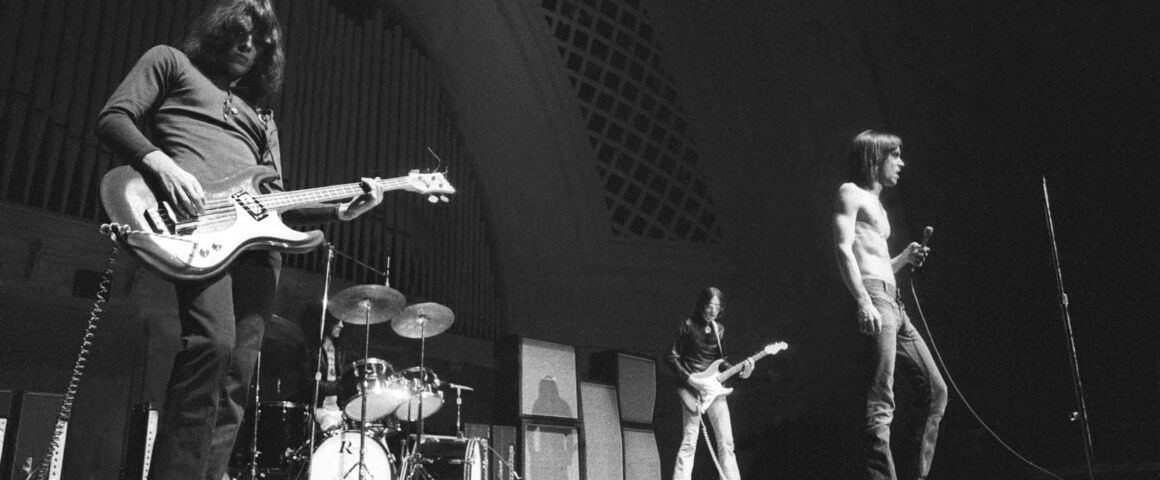

There have been mystics all across time — since the invention of the spirit right at the dawn of matter. They come from the strangest places and settle in the unlikeliest corners. Thus came Iggy Pop, testing the borders that contoured him, piloting the known with the full intention of shaking the ship off, of rushing it to the storm and derail the tides, crash them into the pits, and healing it all by way of negation, by way of the no. What he did with that anti-band called The Stooges was an act of negation of content by the introduction of discontent: “No, that’s not enough.” Seeking is destroying the definitions that contain the shapes by which we guide our actions, model our behaviors.

Iggy affirmed life, but this affirmation came always by way of stating what life was not: “Music is life, and life is not a business,” he says as he and his mates are inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Ironic indeed. This, however, was the creed by which The Stooges lived and, more importantly, by which they died: No Business. NO. POP. An explosion to end all markets, “to avoid everything” and to avow what they really were: Dirt. It was then that they were able to embrace being dirtier and dirtier, and then get clean: A purified being swimming in guts, pushing the entrance by plunging through its entrails. There’s self-reflection as an act of self-mutilation — immolation in the name of a whole generation swamped in naiveté.

Jim Jarmusch approaches this mystical world in his most recent documentary, Gimme Danger — and he does it safe onshore, with an Osterberg (Pop’s given surname) now confident enough to share what was his seven year romp breaking into the hither side of silence by means of breaking its eardrums. Jarmusch then sets to frame this chronicle as a tribute to a man who subjected himself to continued blasts, notably attaching them to his character’s last name, as though the Bing Bang itself were in his direct line of ancestry, and who offered himself to rapid destruction, to self-consumption, just for noise’s sake, something which was, nonetheless, all for the sake of silence. And then we see him, Iggy, them, The Stooges, reaching that natural point of exhaustion stemming from any scheduled sequence of frenzied detonations. And then we see him, them breaking apart in the only way in which explosions are truly stopped: By letting them age. Pop.

So Jarmusch, as an obedient disciple, decides to take no risks in telling the story of a band that refused to be anything other than amateurs — at any cost. As we see 20 minutes into the film, that often meant being homeless, hungry and broke. But that’s the key. If music is life, life cannot be lived professionally, as life is destined for the dilettantes. Life is not meant to make a living, for the price of being alive is only to be determined by those who are willing to defy it with their own deaths, by those who are courageous enough to systematically fail and lose. Onstage, very few have seen their deaths with as much rage as Iggy and his Stooges did, and with as much poise. At every gig, we see, they spotted their own demise as well as the demise of their journey — and they never shied from seeking it.

With no risks on sight, Gimme Danger draws the chronology of a band that embraced failure with the same commitment with which they embraced their end. We get to see then what in most biographical documentaries is pertinent and we look at Osterberg’s childhood spent at the outskirts of Ann Arbor, Michigan, living in a trailer with two parents who were wise (or indifferent) enough to feed their child’s tendencies, who let him overtake the master bedroom so that he could set his drum kit and bang his way through the household’s soundtrack. We also brush through his childhood influences, mainly from TV shows, and of course that alt haiku rule he learned from “Soupy Sales” of writing 25-word-or-less letters (take that Twitter), a rule he took all the way to his lyric-writing, praying with his vowels — chanting with his bowels. What we learn, though, is that his true luck consisted in having being born and brought up in quite a simple environment, as simple as it gets.

Then we go through Osterberg’s first steps towards success, which he kind of mixes with his passion for noise, and his first gigs with his first band, The Iguanas, the music of whom was instrumental in (literally) bringing down the venue that hosted their first gig — hostage of the rubble, scraps of sound competing with the spurting debris. We see how he leaves the parental home to Chicago so as to catch a “little glimpse of a deeper life,” a life of adults who didn’t have to lose their childhood, jazzists, which took him to his life’s greatest realization: He was not black. It is this realization that would carve the deepest cracks in rock history and in popular culture, for The Stooges’ sound would be the first in rock music that owed nothing to R&B, the first that, being so uprooted, would stem from the very innards of noise itself: And second came punk.

We now know that Iggy never really became what he initially wanted: The “black man for his white generation.” Rather, Iggy turned into a self-appointed white-trash banner who took no shame in his (grass)roots. This is why meeting the Ashtons would prove so important in the arch of this story (where animation a la “Paranoid Android” sifts through the narrative — fun though too deliberately teenish): They are Iggy’s perfect allies. The Ashtons quickly prove they are outsiders with no roots to wave, suburban outlaws who weren’t too thrilled about being white either. Then the band, the music, the playing, that is all anecdotal — it all originates out of them saying they had won before they had done any playing. As most punk bands would do after, The Stooges came out of a bluff; they thus coined punk’s creed: Doing before knowing, doing as a result of not knowing — knowing after the fact.

It should be pointed out, though, that the side interviews that Jarmusch decides to shuffle in his film add little to Osterberg’s masterful storytelling — it would have brought better results had he let it all be one, big interview, entirely narrated with that deep, coarse, demonic voice of his. His register is as vast as his influences, and just as eclectic. To Howdy Doody and John Coltrane we need to add The Velvet Underground and John Cage and Harry Partch. This latter was seminal in the early sound of The Stooges (and Iggy’s later in his career, though Gimme Danger doesn’t go that far), in the free flow looping intervals that would create those repetitive themes that contained infinities in less than three minute baselines.

Thus The Stooges became the psychedelic version of the other stooges, that threesome of comedic lunatics, and pioneered glam rock with it, if, as happens with true pioneers, they did so by showing us the end product in its primitive, raw form. When we get to see Iggy onstage, surfing and diving the crowd in-between musical seizures, we see human expression at its rawest. The music was the perfect company to his dancing, a maddened melopea that kept everyone on track, even when, particularly when, they played at the studio. The Stooges’ music is a centripetal force that transcends nihilism yet overwhelms engagement.

This music, of course, too raw, too coarse, was no good for showbiz, which, as Osterberg points out, “is no friendly place.” The industry he portrays (which Jarmusch does little to dig in; he knows it all too well) is a corrupt lair where life is sucked dry and culture is a matter of treason, an industry that, in his words, prefabricated peace and love, that soapy hippie stuff that, to his nose, “smells, still smells.”

And here’s where the divide between mystic and public person sinks in, if you haven’t nosed it yet. Affirmation through the road of negation is only non-toxic in that other realm that pertains not to the material world, be it spirituality, art, poetry, faith, religion, or all of the above (or some). When these same features are transferred to the realm of bodies, of bodies living with each other, to the public world, they are inevitably fated to be corrupted, tainted, and end-up in destructiveness: Authoritarianism. That’s why we need mystics, true artists, true poets, true priests, to take this centripetal journey so that the public life can gain in depth without having to experiment with excess, rifts, violence . . . extremism. The road back to public life, as Gimme Danger aptly illustrates through the voice of his storyteller (a survivor who has outlived many of his contemporaries, notably the other two amigos, Lou Reed and David Bowie, and is still quite productive), has to be done with caution, with utmost care, and very, very slowly — with the patience that only time gives.

35 years after, The Stooges reunited (inspired by the 1998 little cult film, “Velvet Goldmine,” inspired, in turn, by The Stooges) in 2013. It was a true reunification. It was then that they took the opportunity to “do the right thing 35 years after.” What’s the right thing? The impossible: Getting to manage all those forces, centripetal as they are, without tearing one’s own body apart. That’s how he opens and closes the film, Osterberg, Iggy: In a calm, sedated action packed in raging rants, jabs against an aging angst — jabs with eyes closed. No sight. No — tnemethgilnE — or its flip side — si eh ereht — the zen master of punk — achieving absolute selflessness.

'Movie Review: Gimme Danger (2016)' has 1 comment

November 10, 2016 @ 7:00 pm okay_bloke

I hope Iggy Pop, Keith Richards and Ozzy Osbourne donate their bodies to science when they die. The secrets to their longevity must be discovered.