Late filmmaker Horace B. Jenkins’ early eighties African-American racially driven romantic drama Cane River gets a new lease on life with its millennium-era restored release nearly four decades after its attempted initial run. Indeed, Cane River epitomizes the smooth, but potently observational, character study of black division and togetherness — all under the complicated umbrella of love, cultural traditions and biased Southern class self-identification. Rich in resonance and thoroughly revealing in its absolute truth, writer-director Jenkins delivered an absorbing black romancer that delves into the psyche of blackness and belonging.

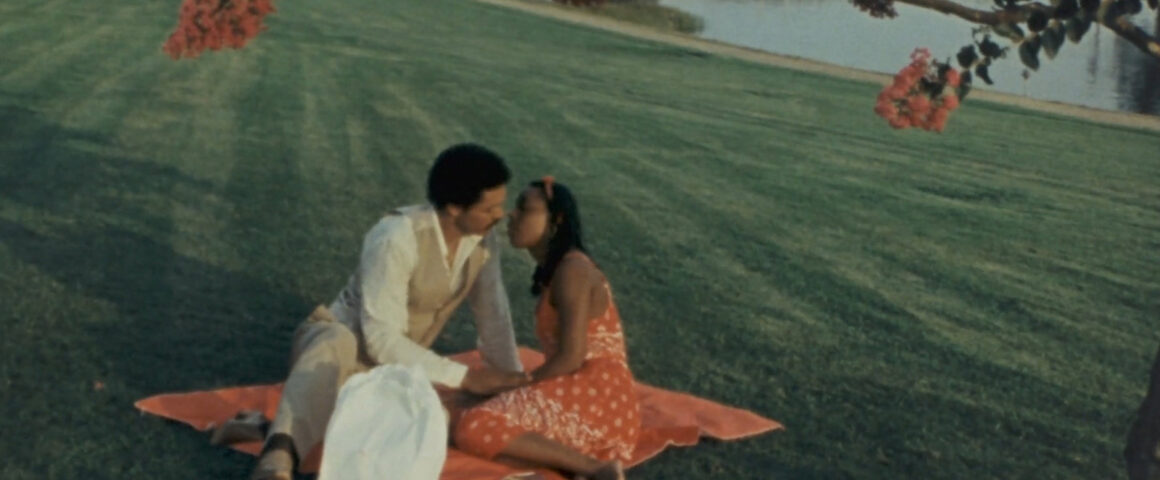

Fittingly, Cane River emerges in the month of February as it encapsulates the celebrated awareness of both Black History and the moodiness of love in the affectionate realm of St. Valentine’s Day. The romanticism involves Louisiana products Peter Metoyer (Richard Romain, “Great, My Parents Are Divorcing!”) and Maria Mathis (Tommye Myrick, “Woman Thou Art Loosed: On the 7th Day”) — a devoted couple that come from two completely different backgrounds in family dynamics, financial backing, and sadly . . . colorism restraints. Given their so-called differences, Peter and Maria are solidly bonded — or try to keep close emotionally and financially in the close knit community of River Cane, Louisiana. The concept of status is crucial to the mindset of the families that Peter and Maria represent.

For Peter, the expectations are high for his particular pedigree in the community. Tall, handsome, light-skinned and educated, the athletic Peter is part of Cane River’s prominent leading family of farmers. The Creole-blooded poet Peter had a promising future playing big-time NFL football but opted to return to the prosperous family farm instead. Peter hails from a mixed race bloodline of French lineage and enslaved blacks and his swirling ancestry seems to give him both convenient clout and casual privilege. The poetry reading and writing under the shady tree and horseback riding around the scenic greenery landscape certainly lets us know how advantageous it is to be a Metoyer in Cane River.

As for Maria, she is a dark-skinned beauty whose working class credentials as a tour guide for plantation attractions vastly differs from Peter’s comfy existence. Maria desperately wants to escape the menial life she leads locally and head off to college in hopes of a brighter, secure future. Maria’s familial roots are entrenched in the horrible histrionics of African slaves that leads to her impoverished leanings of today. She does not have the flexibility of European mixture automatically making her worthy in the shadows of Louisiana’s black color-crazy mentality. Maria’s only family-oriented strength lies in the unconditional love of her equally destitute, blue-collar working mother/brother “prisoners” (Carol Sutton, “Out of Blue” and Ilunga Adell).

So the template is set for the fussing and fuming bewteen the romancing of fair-skinned “golden boy” Peter Metoyer and working stiff ebony queen Maria Mathis. Peter is a Creole. Maria is a Natchitoche. Peter is a Catholic. Maria is a Protestant. Superior Peter is considered a “wonderful catch” for any woman wanting his admiration. Inferior Maria has the nerve to capture the heart and soul of the farming heartthrob. Education was just a path for Peter to follow his exceptional journey that he declined by choice. Education is the ideal stepping stone for Maria to break away from the doldrums within restrictive Cane River. Cane River is a comfort zone for the welcomed Peter. Cane River is a suffocating small haven for Maria. Peter is impervious to the backlash surrounding his love for low-income Maria. Maria, on the other hand, is receiving continuous static for her placed intimacy aimed at Peter from family and busy body commentators alike.

Long before resourceful filmmaker Spike Lee dropped some cinematic absolution for explosive films that touched upon black empowerment issues, race relations, and stigmatized colorism exploration (“Do the Right Thing,” “School Daze,” “Jungle Fever,” etc.), Jenkins candidly exposed the low-key tensions of a black southern community rocked by the haunting echoes of a nightmarish past in an unforgiving America that has poisoned and positioned a disfranchised people of color through generational disorientation. There is nothing revolutionary in terms of the acting, production brilliance or any breakthrough messaging. Still, Cane River makes for an eye-opening revelation about the psychological and mental affliction that still permeates in contemporary, cynical black society.

It is too bad that Jenkins passed away shortly after the completion of Cane River because it would have been very interesting to see how this promising and insightful movie-maker could have contributed to the respectable genre of engaging independent film-making at its most thought-provoking level of consciousness.