As you get immersed in the world of Loving Vincent you quickly realize that it is not the shiny technique alone that makes you feel as though you were floating inside Vincent van Gogh’s brushstrokes, but that, as happens with his painting, there is a profound love for the subject driving each and every frame of this film. On the surface then, the shiny gimmick of creating a moving picture out of animating the artist’s art and work, eyes and hands, would wear down quickly if it not were because, as we approach the flattened textures that illuminate the picture, we are struck by light, and the lighting bulb that announces all realizations settles down through the virtual canvas in which the screen has become, and we’re delighted by the love the filmmakers show for their subject, comparable to the love the painter felt for his.

Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman’s biopic is, quite literally, a portrait. Yet, this portrait is not exactly of one person, nor is the biopic, if truly it is of one body, a body of work. van Gogh, we know, worked on a frenzy to leave one of the most voluminous body of works ever recorded, particularly when taking into consideration he did it all in no more than eight years. This frenzy is precisely one of the main attributes used to create the archetype of the mad genius. The other attribute, of equal weight in the painter’s archetypal character, comes after his self-inflicted wound that left him agonizing for days and had him dying a horribly painful death. It is from here that the archetype of the tortured artist was stamped over van Gogh synecdoche, the figure of speech to which all archetypes go to die.

Loving Vincent explores the life and death of the painter by looking into the last days of his life. It sets to dispel, or at least put into question, the dark crevices of despair that drove him increasingly forlorn and, ultimately (and untimely), suicidal. By doing this, the film also sheds light to the nature of his work; yes, he was a genius, but that played very little a role in his desire to paint everything he saw. Suddenly the frenzy is perceived as nothing but hard work, and a harder work ethic.

Thus, what most clearly comes across in this film is that Vincent (Robert Gulaczyk) was a man in love with the world, and hence a man who could appreciate beauty in everything at all times. Echoed by the filmmaking, all his canvas were portraits, because he made no distinction between subjects, whether humans or flowers or crabs or shoes or chairs or stars. Stared he did. He dared to look in every subject the subtle changes that made them different every time he gazed at them, every time he blinked. How can a person so much in love with the world would want to end his own stay in it?

The previous paragraphs, however, should not tempt us to go the other side. The man had issues, and those were deep-seated in his psyche. As much as he could eloquently express himself through the transformational resources of art, he found it hard to express anything at all to the people around him. Sometimes it feels as though his flesh was more an impediment than a bliss, and one wonders how many times was that flesh felt and touched with a tenderness comparable to the one he had inside for his surroundings. And this is one of the smartest moves in Loving Vincent, as those last days are recounted by little episodes conveyed through conversations with other people, all villagers cognizant of their eccentric, if mostly amenable, visitor. This sort of spectral narrator (similar to the narrator in Malcolm Lowry’s schizoid, yet exquisite, “Under the Volcano”), continuously flying from voice to voice, person to person, weaving all episodes together, is what gives the film its dream-like quality, and furthermore, its afterlife quiddity.

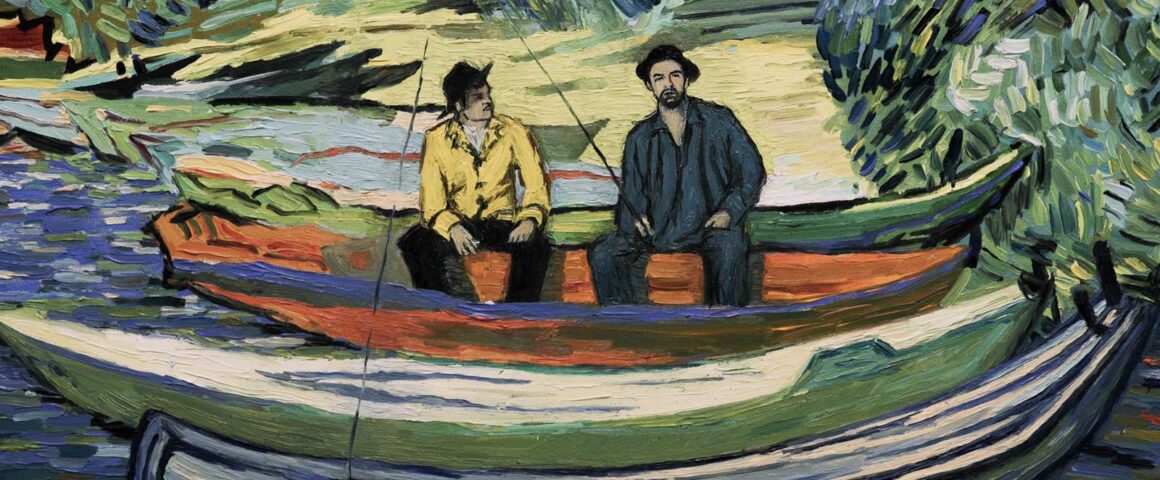

The other part, what could be considered the “plot,” the telling of which I have been delaying for more than a page, is the more prosaic line of the film. It follows the rather unmotivated Armand Roulin (Douglas Booth, “The Limehouse Golem”), an acquaintance by proxy of the Dutch painter, as he tracks the traces of Theo (Cezary Lukaszewicz, “Belfer” TV series), his brother and patron, to deliver what was the last letter he wrote to him. Armand’s father, the very respectable Postman Joseph Roulin (Chris O’Dowd, “St. Vincent”), is actually the one who assigns the task to his son (after dragging him out of a low-brow bar) and who first plants the seeds of the mystery that then unfolds.

How could a man who seemed to be in such good spirits just a couple of weeks before commit suicide? The Postman’s drive is to understand the depths of what happened to his admired customer during those final days. Unfortunately, what the son gets is the drive to understand an unveiling mystery that, not even well into the second act, has become altogether inconsequential. Did van Gogh shoot himself or was he shot? Was it suicide or murder or, even more, a conspiracy of sorts? The reality is that it doesn’t matter at all.

This mystery brings a “Citizen Kane”-esque narrative, with a person on a task trying to reconstruct the figure of a man through the testimonies of those around him (a whole bunch of people in the little village of Auvers-sur-Oise, just at the outskirts of Paris, France). Each interviewee paints a different picture of the man, with only one perfect constant binding together all accounts: The man worked and worked and worked. When he wasn’t painting, he was writing; everything else, drinking, sleeping, eating, getting drunk, getting laid (and failing on it), was done almost simultaneous to his work.

Again, by having a dead man at the center of every conversation, a ghostly thread relating all voices, the spectral narrative on which Loving Vincent relies gives (and gifts) the film, each of those tens of thousands hand-painted frames, an afterlife anima, like the staring eye of a hurricane. It is as though Vincent himself was bearing witness to the drama of his recent demise, and we can picture him, sometimes perhaps, enjoying himself with the exercise.

And this is where the film thrives, where the epic effort of its technique is not overshadowed by the superficiality of its own conceit. Each frame is soaked in the vision of a person who has recently left this world, lifting himself as dust subjected to the currents of other people’s voices. A silent vision. And a lonely one. Because that’s the other common theme across accounts; he was such a lonely man — lonely to a melancholic pole.

It is quite possible that such loneliness could be converted into the vacuous gravitas of a tragic figure — it is even tempting. But things are more complex than that, and the directors decide to refrain from any attempt at explaining the causes behind Vincent’s loneliness or at establishing any causal relation to quickly rush into the under-appreciation that haunted the painter his whole life. He just was, both lonely and underappreciated. Yet who are we (the people talking, the people viewing, and the people putting this film together) to speak on his behalf? The border between telling stories (or relating anecdotes) and analyzing characters is yet another well-drawn line, another on-spot stroke.

And what else did van Gogh bestowed upon our eyes and gazes and visions if not strokes. Each a piece of afterlife, a line on the face of nothingness. Each glowing the life that lies beyond the realm of matter and yet each celebrating the physical beauty of every body around. Each stroke is a shooting star in the night of existence. A day borrowed to eternity. A night given to the great beyond. The light that dwells its own aftermath bears witness to the birth of its own myth.

'Movie Review: Loving Vincent (2017)' has no comments