Sometime in the 1990s, somewhere in Toronto, in the scuzzy Gemini Motel, a prostitute is raped. She becomes pregnant. Overcome with grief, she kills herself. Cut to 23 years later, and it seems the baby survived.

Helen (Alanna LeVierge, “Mia and Me” TV series) is at a loss in the world. She’s drawn to the motel because it feels “safe.” But Helen isn’t safe, and her torment lies within herself. She is suffering absences, and possibly sleepwalking. Her would-be lover, Roman (Michael Lipka, “Tormented”), gives her a very creepy painting, depicting her not just naked but skinless.

Helen’s best friend, Molly (Nina Kiri, “The Haunted House on Kirby Road”), is scared, and encourages Helen to seek help. An MRI scan reveals there is something very unusual growing in Helen’s brain. She has three days until surgery; until her nightmare is over. Can she survive long enough?

Part body horror and part slasher, Let Her Out is about our fear of madness; of losing control. And, like (the admittedly superior) “It Follows,” the film offers a peculiarly female focus on the fear of invasion and infection.

After a shaky start, replete with disappointing jump scares and loud noises, the film’s mid-section is expertly handled, as temporal and spatial rules begin falling away. Here, we get a real sense of Helen’s emerging madness: The frustration and ambiguity of not knowing if what she’s seeing is real or imagined. Her absences are jolting and disorienting, and we really feel it: The horror of waking up in a dangerous, and sometimes humiliating, situation. After a while, the blackouts bleed into her waking world.

This central portion of Let Her Out is cleverly edited, so our allegiances are dragged this way and that. Characters who at once seemed lecherous or selfish, we realize, may actually have been spurned lovers or spurned friends. Chronology is confused, so that what we sense can’t be trusted — it may have happened, or it may be some competing, phantom desire residing in Helen.

Even if some of the performances are a tad wooden, the characterization remains strong throughout. I particularly enjoyed the disgustingly toxic relationship between Helen and theater director Ed (Adam Christie, “Weak Ends”). They share a great scene in an alleyway, both sad and slyly witty, in which Helen offers up a withering rebuke to his masculine entitlement.

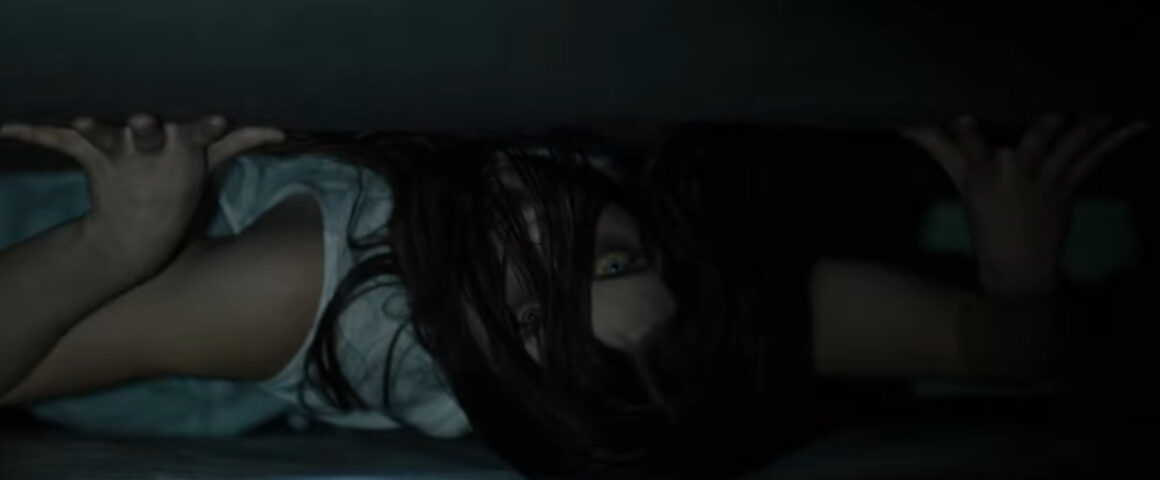

Let Her Out finally succumbs to trad slasher tropes, with a bit of contortionist possession stuff thrown in for good measure — but even then, director Cody Calahan (known for his “Antisocial” films) throws in a real humdinger of a transformation scene. Hats off to Shaun Hunter, the maestro who redefines the idea of “skin-crawling” here.

Calahan clearly knows his inspirations. The mention of Canadian body horror evokes one gigantic auteur, and Calahan occasionally manages images worthy of David Cronenberg. Suffice to say, it’s not enough to tear out the stitches — there’s got to be something stuffed inside the wound, right? Later, an effectively ghostly scene sees Helen shaking away her vision and talking to herself like Danny Torrance confronted with the Grady girls, in Stanley Kubrick’s “The Shining.”

Uttering Calahan’s name in the same breath as such greats might be over-egging it. Let Her Out doesn’t have the poise or resonance of its classic touchstones. Too often Calahan shows a lack of faith in the simple creeping discomfort of body horror — or its mere ickiness — so he feels the need to throw in a crash cut or hack up his images with over-fussy editing.

Which is a pity, because there are some genuinely memorable and eerie sights: A face contorted in a scream behind a shower curtain; Helen running down a street which is sliced by light, half amber and half blue; a dead-eyed phantom in an alleyway, rapidly breathing, only her face clad in deathly grey.

Throughout, Calahan musters a satisfying neon-nightmare mood, not unlike Franck Khalfoun’s 2012 “Maniac” remake. His use of lighting is particularly bold, whether it’s the bloody red of Helen’s bedroom, the sickly yellow of a parking garage, or the drowned blue of an overwhelming house party. It’s also fantastically grisly and graphic: During one subway scene, the camera seems to avert its gaze — only to return to the scene of the crime, as if morbidly fascinated.

As is en vogue, composer Steph Copeland’s music is a woozy selection of dark synth, perfectly complementing the neon-piped credits font, but not always ideal for the action on the screen. Copeland’s score is unrelenting, often overbearing, and sometimes downright intrusive. A scene in which a character is terrorized by the sound of squealing fingertips on the bodywork of her car is brilliantly framed and edited, but begs for quiet.

Let Her Out does little truly new, but it’s a very well made and properly nasty horror film, which sustains a compelling intensity, and whose storytelling is brisk and efficient. With a braver script, willing to take us all the way to the end of Helen’s pitch-dark rainbow, and little more directorial and editorial discipline, and we may yet come to regard Cody Calahan as a Canadian upstart capable of following in Mr. Cronenberg’s bloody footsteps.

'Movie Review: Let Her Out (2016)' has no comments